By Duane Porter

Nothing distinguishes memories from ordinary moments. It is only later that they claim remembrance. By their scars. — Chris Marker, La Jetée

.

Writer, editor, photographer, filmmaker, world traveler, archivist and multimedia/installation artist, unclassifiable and without boundaries. Born Christian-François Bouche-Villeneuve on 29 July 1921 at Neuilly-sur-Seine, an exclusive suburb of Paris, Chris Marker has sought to circumvent the expectations and limitations associated with background and class by choosing a name that might belong to anyone and that is easily pronounced anywhere. Working under various pseudonyms, avoiding interviews and photographs, and being somewhat evasive regarding his biography, Marker maintained a certain level of anonymity that has proved useful in his work. Beginning in January 1947, he published poems, short stories, and essays in the eclectic intellectual journal, Esprit. Also among his early works are one novel, Le Coeur net (1949), about airmail pilots in Indo-China after the war, and a critical monograph of playwright Jean Giraudoux (1952). He became increasingly interested in film, writing essays on Laurence Olivier’s Henry V, Cocteau’s Orphée, and Carl Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, among others. Having mastered the personal essay, inspired by a love for word and image, he ventured into filmmaking with Olympia 52 (1952), an account of the Helsinki Olympic Games. His second film was actually his first, begun two years before Olympia 52 but not finished until one year after, Statues Also Die (1953), co-directed with his friend, Alain Resnais. Being about African art and the effects of colonialism on traditional cultures, it was banned by the French government for its criticisms of colonialism and wasn’t seen in it’s entirety until 1968. Several distinctive essayistic travel documentaries followed, A Sunday in Peking (1956), Letter from Siberia (1958), Description of a Struggle (1960), and Cuba sí! (1961), firmly establishing his association with the essay film. Marker considers his work up to this time to be merely a rough draft, maintaining that his filmmaking career began in 1962 when he began work on Le jolie mai (1963), an intimate interrogatory account of Paris during May 1962 in the days following the close of the Algerian War. It was during breaks in the shooting for Le jolie mai that he made most of the photographs that make up La Jetée, a 27 minute post-apocalyptic love story made up almost entirely of black and white still photographs. A meditation on time and memory that is also a reflection on the nature of the photographic image. A photograph being a perception of immediate reality, an image of the present that instantly becomes the past, a photograph is always a memory.

The roar of jet engines fills our ears as the camera backs away to show the passenger planes lined up alongside the observation pier of the Paris Orly Airport. The voices of a choir (Choir of St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral performing music from Russian Liturgy of the Good Saturday) drown out the noise of the jet airliners and create a mood of respectful awe as the credits come to a close. The screen goes black for a second and a white intertitle appears:

Ceci est l’histoire d’un homme marqué par une image d’enfance

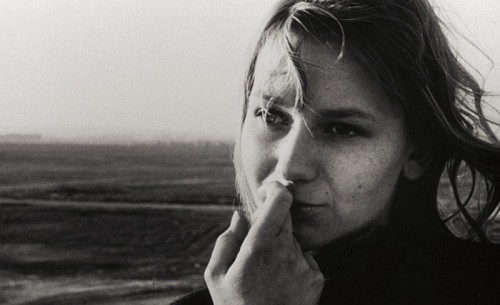

A man’s voiceover (Jean Négroni in French or William Klein in English) reads: “This is the story of a man, marked by an image of his childhood.” We are shown a sequence of still photographs of the airport as the voice informs us that the man he is speaking of has a memory of beauty and violence that happened here on a Sunday before the war when he accompanied his parents to watch the planes take off. He remembers the day was cold and the setting sun shone through the hazy sky on the face of a woman (Hélène Chatelain) standing near the railing. Suddenly, a loud noise, the woman puts her hands to her face, a man falls and the crowd lets out a cry of alarm. Later, he realizes that he must have witnessed a man’s death.

In the time after the war, after the destruction of Paris, survivors found shelter from the radiation that enveloped the city by taking refuge in the rooms and passageways beneath the Palais de Chaillot. Some of the survivors assumed control and made prisoners of the others. Using the prisoners as guinea pigs, experiments were conducted that yielded only death or madness. The experimenters then picked a man (Davos Hanich) who they knew possessed an intense memory that recurred often in his dreams. The man in charge (Jacques Ledoux) explained that since they were trapped by the radiation on the earth’s surface and effectively unable to move about in space the only option left for them is to travel through time. If he can succeed in returning to the past, back to the time of his memory, then he just might be able to reach help by traveling forward into the future. Using a combination of drugs and sensory deprivation, the scientists consulting among themselves whispering in German, the experiments went on for days. His heart is heard beating strongly and ever more rapidly as the procedure continues. Nearing the point where the others had failed, his memory remains strong and on the tenth day he begins to see images of a time before the war, a bedroom, birds, a child, a cat, a graveyard. On the sixteenth day he is at the Orly Airport and he glimpses a girl. Could she be the one? The experiments continue, and on the thirtieth day he sees her again, her hair pinned in a spiral at the back of her head. He follows her into a flower shop and while he is momentarily distracted by the opulence around him she disappears. The experimenters send him back and this time he is standing beside her. They are gently wrapped in a haunting melody (score by Trevor Duncan). They speak, she is unalarmed. They walk in a garden, the music softly swells. They are standing in front of a display with a cross section from a giant sequoia tree marked with historical dates. He finds himself pointing to a place outside the tree and says, “That’s where I come from.” In the coming days, they are together. He tells her he comes from far away. She calls him her ‘ghost’. He watches her sleep, a crescendo of birdsong comes through an open window, she awakes, blinks her eyes and smiles.

A day comes when the experimenters decide that he is ready to go into the future. This is much more difficult, he suffers and endures and succeeds. The people of the future, learning of the precarious state of humankind, realize that their own existence must mean humanity will survive this crisis and they know they must help him. They send him back with a power module strong enough to ensure survival. Now confined to the camp, he comes to realize that he is no longer needed and fears he will soon face liquidation. The beings from the future are capable of moving through time with ease and, sensing his fear, offer him a place with them. But he cannot forget the face he left behind. Once again he is on the pier of the Orly Airport. He sees her standing at the railing and begins to run toward her when he recognizes a guard from the camp who has followed him here. With the voices of the choir rising, she turns and sees him falling and puts her hands to her face.

1962 was the time of the cold war and the nuclear arms race between Russia and the United States with the Cuban Missile Crisis occurring during October of that year. World War III and the fear of nuclear holocaust was on everyone’s mind, but in La Jetée these things merely provide a backdrop for a story that is about something altogether different. In Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), after Madeleine’s death, Scottie is obsessed with her memory and is driven by a desire to turn Judy into the image in his mind. Marker has said that La Jetée is his remake of Vertigo, a film he claims to have seen more than 20 times. His cinephilic attachment to the image of Madeleine forever haunts him, he wants to be with her, and La Jetée is his personal search for Madeleine. The scene in the flower shop where the girl appears with her hair pinned up in a spiral echos the scene in Vertigo where Scottie spies on Madeleine in the Podesta Baldocchi florist shop. And, more explicitly, the scene of the redwood display matches the scene where Madeleine, standing before a similar exhibit, extends her gloved hand and points to the tree rings and says, “Here I was born … and there I died.”

Ever since it’s earliest days, and surely most compellingly, since the revelation of Dreyer’s camera close to the face of Maria Falconetti, cinema has been ‘totally, tenderly, tragically’ enthralled with the face of a woman. Whether it be Simone Genevois in La Merveilleuse Vie de Jeanne d’Arc (1929), for Marker first seeing this when he was seven years old “a face filling the screen was suddenly the most precious thing in the world,” or it be Falconetti or Louise Brooks or Kim Novak, as he puts it, “a film without a woman is still as incomprehensible . . . as an opera without music.” Hélène Chatelain’s, awakening in La Jetée is one of the most remarkable moments in all of cinema, a sequence of dissolves cause the still images to melt one into another until – an instant of motion – the fluttering of her eyelids, a twitch at the corners of her mouth, she looks directly into the camera and smiles. These six seconds are perhaps the most eloquent reflection on the nature of cinema that we have. Marker has always been interested in mixed media, juxtaposing image and text in several early books and films. The credits at the beginning of La Jetée acknowledge it’s intersecting nature by identifying it as a photo-roman, or photo novel. The still photographs, intertitles, voiceover, filmed sequence, sounds and music come together to form a multimedia investigation of the medium itself. The illusion of movement in cinema is created by passing a sequence of images through a projector at the speed of 24 frames per second. La Jetée uses sequences that contain dozens of identical images to create an illusion of stillness. The stillness is then animated using camera movements and rhythmic editing, cross-fades, dissolves, and cuts to black (edited by Jean Ravel). This dialogue between stillness and motion gives La Jetée its particular insight into the multivalent character of cinema making it one of the great films about film.

Although La Jetée is generally considered to be Marker’s only work of narrative fiction it has close connections with two of his other films, Sans Soleil and Level 5. The three can be seen as forming a trilogy on the theme of time and memory, seeking to reremember or rewrite the past, evoking the themes of Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944), Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour (1959) and Last Year at Marienbad (1961) and Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Sans Soleil (1983), appears to be a travel film in the form of a cinematic essay that starts out in Iceland in 1965, moves forward to the 1980s alternating between Japan and Africa, and ending up back in Iceland. Sandor Krasna, a semifictional filmmaker, has written of his travels over many years in letters to a woman, the semifictional narrator (Alexandra Stewart), who reads them to accompany the images. “The first image he told me about was of three children on a road in Iceland, in 1965. He said that for him it was the image of happiness . . . ” This opening image of happiness is contrasted against black leader, perhaps a comment on the fragility of happiness. “I’ve been round the world several times and now only banality still interests me.” Considering the everyday, people sleeping in their seats on a ferry – smoking – waiting, he seeks to interrupt the everydayness by transforming the everyday. Sei Shōnagon, lady in waiting to the Japanese Empress Teishi during the tenth-century, was also a writer with a passion for list making. Her list of ‘things that quicken the heart’ becomes Marker’s criteria for where to aim his camera. “Have you ever heard of anything more stupid than what they teach at film school—not to look at the camera?” And what he is really after, as when in La Jetée Hélène Chatelain awakes, is the transcendent moment when the eyes of the person being filmed look into his lens and, in turn, the eyes of the spectator. Still images from Hitchcock’s Vertigo are shown as Krasna makes a side trip to San Francisco as a sort of cinematic pilgrimage to seek out the locations used in the film. The Podesta Baldocchi flower shop, the cemetery at Mission Dolores, the Museum at the Legion of Honor, the sequoia in Muir Woods, and the mission at San Juan Bautista. It was here that Scottie learned, as did the man in La Jetée, there is no escape from time. Sans Soleil attempts to move outside space and time using a different method. Another semifictional character, Hayao Yamaneko, a video technician, uses a computerized synthesizer to alter images as a means to bring the past into the present. Photographs of past events become abstractions, leaving only their essence. They now exist as pure images in a realm he calls ‘The Zone’ (named after a place in Tarkovsky’s Stalker [1979] where physical laws do not apply) rather than as remembrances of things that no longer exist. As Hayao puts it, “at least they proclaim themselves to be what they are: images, not the portable and compact form of an already inaccessible reality.” Even so, Krasna, the cameraman, continues shooting film, adding to his archive of images, poignantly aware of ‘the impermanence of things’ and the forgetting incurred by the passage of time, these images will take the place of memories. Krasna wrote, “I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting, but rather its lining. We do not remember, we rewrite memory much as history is rewritten.”

In Level 5, a woman (Catherine Belkhodja) sits alone in front of a computer. “What can these be but the playthings of a mad God . . .” she says to her lost love, remembering something he once said. The camera holds her face, she continues talking to him, making entries in her video journal. She is trying to complete the development of a video game that was his last project, the Battle of Okinawa, a game of strategy, but unlike other strategy games that look for alternative outcomes, the object of this game is the recreation of historical events as they actually happened in order to correct the historical record. The computer thus becomes the moral arbiter that will not allow an alternate telling of the story. She conducts her research over a science-fictional proto-internet network called Optional World Link (OWL). Here she finds interviews with survivors and other witnesses as well as documentary footage, adding each piece to the unfinished puzzle. Level five in the game can only be reached by adding all the correct data and completing the story. Unfortunately, much has been lost to time and human intervention leaving level five unattainable. The mourning intimacy of her journal entries intercut with the pieces of evidence she has found attesting to the atrocity set in stark relieve what this film hopes to achieve. Level 5 seeks to rewrite history and tell the story of a massacre, mass suicide, sacrifice (more than 250,000 people died, including 100,000 Japanese soldiers, 12,000 U.S. soldiers, and 150,000 Okinawan civilians), one of the great atrocities of the 20th Century, unmentioned in the official history books in the U.S. and in Japan. The devastating outcome of the Battle of Okinawa (April – June 1945) led directly to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (August 6 and 9, 1945). Japanese filmmaker Nagisa Oshima insists that the Japanese government knew they could not win this battle and willingly sacrificed the island’s population. The people were told not to surrender to the Americans, that it would be better to die than to be taken prisoner, they then were given grenades to help them commit suicide and suicide/murder. One witness, Kinjo Shigeaki tells of how he and his brother killed his mother and younger siblings to keep them from falling into the hands of the American soldiers.

He called her Laura. She remembers when they saw a movie together in Japan, Otto Preminger’s Laura. That was when he first called her Laura. That was when she became Laura. Now, evoking the image of Gene Tierney, she takes out the sheet music for the movie’s theme song (composed by David Raksin with lyrics by Johnny Mercer) and begins to softly sing, “Laura is the face in the misty light . . .” Now she wonders, “Am I going mad? I used to see you everywhere, I recognized you from afar, I went back to the places we loved, the Jardin des Plantes, the little farm at the Bois de Boulogne, the shore beneath the Golden Gate where Kim Novak feigns suicide in Vertigo, I’d see a man from behind, looking at parrots or sitting among goats or leaning against a rail, and it would be you, then I’d come closer, he’d turn round, be someone else, I’d wonder how anyone, could replace you so fast?” Her memories of Preminger’s Laura, the footsteps that you hear down the hall, echo across decades with Hitchcock’s Madeleine, her hair a chignon spiral of time, each one interlaced with the other, transporting us back to another little madeleine, a scallop-shell pastry from northeastern France, and a cup of tea. À la recherche du temps perdu (Remembrance of Things Past or more literally, In Search of Lost Time), Marcel Proust’s monumental novel, is the ultimate meditation on memory.and consciousness:

No sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. . . . And suddenly the memory returns. The taste was that of the little crumb of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good day to her in her bedroom, my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it. And all from my cup of tea.. . . But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more immaterial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection. — Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, (1913–1927)

Okinawa mon amour. The past is past, there is no escaping time. Laura realizes that the game could never change history, that history will continue playing in an endless loop, that she can never get to level five. “I had it on the tip of my tongue,” she laments. She loses interest, becomes detached. Disappearing, she leaves all this material for Chris, she calls him the master of montage. Maybe he can do something with it.

Chris Marker, as a life-long supporter of leftist causes, took great interest in the New Left movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Le Fond de l’air est rouge (A Grin Without a Cat), first released in 1976 and again in an updated version in 1993, chronicles the anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist activities of the era. Using Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) as a touchstone, Marker’s brilliant montage, made from his own as well as found footage, mourns the funerals of slain activists, the atrocity of the Vietnam War, the assassination of Che Guevara, the death of Salvador Allende, the invasion of Czechoslovakia, and the end of the New Left. Disillusioned with a revolution that had been in the air but failed to reach the ground, after nearly a decade of working with militant film collectives, he began working on his first multimedia gallery installation, When the Century Took Shape: War and Revolution (1978), two video screens showing archive film of the First World War and the Russian Revolution that had been manipulated into abstract images leaving only a shadow of their history. More installations followed, most notably Zapping Zone: Proposal for an Imaginary Television (1990-94), an electronic montage drawing on his earlier films and photography projects together with more recent work focusing on personal obsessions, a portrait of Chilian artist Roberto Matta, videos of cats, elephants and other animals, travelogues on Tokyo and Berlin, a video of Catherine Belkhodja in the Château de Sauvage wildlife park, all displayed on an assemblage of television screens and computer monitors in a darkened room. Another called Silent Movie (1995) celebrates the centenary of cinema using film-clips from pre-1940 films correlated with imaginary silent films featuring Catherine Belkhodja accompanied by recorded piano music and digital posters for films seen only in dreams, a silent era Hiroshima mon amour starring Greta Garbo and Sessue Hayakawa, an early talkie version of Breathless directed by Raoul Walsh and starring Wallace Beery and Bebe Daniels, or best of all, an Ernst Lubitsch silent adaptation of Remembrance of Things Past.

Staring Back (2007), a collection of photographs taken from 1952-2006, was both an exhibit in a gallery, Wexner Center for the Arts (Columbus, Ohio), and a book. Over 200 images, video captures, film stills, and photographs, having been sorted from his extensive archive gathered over a lifetime. First there are the protest demonstrations – the Algerian War, the March on the Pentagon, Paris May ’68, all the way up to the recent ongoing protests over French labor laws. Later the vicissitudes of human experience evoke time passing and the impermanence of memory and remembrance. Perhaps, making images is our only way to guard against forgetting. Between the youthful protests and the fear of forgetting is a section where the images are almost all of people personally engaged with the camera and the camera operator, their eye contact is assured and direct. Marker has said that in his work he has tried to give a voice to those without one, if not for this, he says, he would have been quite content just taking pictures of girls and cats. And as the photograph that appears on the cover of the book version of Staring Back reminds us, everything always comes back to a woman’s face. Christine Aya, a film editor that has worked on some of Marker’s projects, looks into the camera, her head resting on her hand, a cigarette between her fingers. Her gaze open and direct connects with the eyes of the viewer and something very human, a feeling, a recognition, a realization, is communicated across space and time. And then it all ends with several pictures of animals looking as prescient as any of the humans. Combining prints from different periods, forming a juxtaposition of moments of time, as with all his work, Marker’s arrangement of the images here tends to resist sequence and linearity, denying the pervasive demand for narrative.

Chris Marker, a time traveler, a Martian, a large orange tiger-striped cat called Guillaume-en-Égypte, described thus by Alain Resnais, “In fact a theory is making the rounds, and not without some grounds, that Marker could be an extra-terrestrial. He looks like a human, but perhaps he comes from the future or from another planet… There are some very bizarre clues. He is never sick or ill, he is not sensitive to cold, and he doesn’t seem to need any sleep.” Chris Marker passed while working at his computer in Paris on July 29, 2012 at the age of 91. In 2014, Chris Darke, a writer and critic, curated a retrospective exhibition of Chris Marker’s work at Whitechapel Gallery in London. At the time of the making of La Jetée Jacques Ledoux (who portrayed the chief experimenter in the film) was the director of the Royal Belgian Film Archive and it was here that Marker donated the films work materials. For this retrospective, Chris Darke was able to obtain an alternate version of the film as well as a workbook that showed how the narrative sequence of the film had developed. This alternate La Jetée opens with ten seconds of motion showing the man running toward the woman and then as the credits appear the still images begin, a small difference that completely alters the film. On display in the other rooms of the gallery, looped projections of the films were running, there were tables holding the books and the work materials, and the photographs and film stills hung on the walls. The definitive La Jetée was the only film in the exhibition with a dedicated room of its own. A room dimly lit with rows of benches facing a screen leaving room to one side for people to pass through. As the film ran, some would sit as in a theater with rapt attention, others would stop and watch for a few minutes and move on as is typical of gallery viewing, either response ends up being a fitting homage for this artist who knew no boundaries.

Adieu à Guillaume-en-Égypte

References:

Alter, Nora M., Chris Marker (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006).

Cooper, Sarah, Chris Marker (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008).

Darke, Chris and Rashid, Habda (eds.), Chris Marker: A Grin Without a Cat (London:Whitechapel Gallery, 2014).

Darke, Chris, La Jetée (London: Palgrave, 2016).

Harbord, Janet, Chris Marker: La Jetée (London: Afterall, 2009).

Lupton, Catherine, Chris Marker: Memories of the Future (London: Reaktion, 2005).

Marker, Chris, La Jetée: ciné-roman (New York: Zone Books, 2008).

Click on names for archives

Writers/Founders

Click on names for archives

Writers/Founders

Ever since it’s earliest days, and surely most compellingly, since the revelation of Dreyer’s camera close to the face of Maria Falconetti, cinema has been ‘totally, tenderly, tragically’ enthralled with the face of a woman. Whether it be Simone Genevois in La Merveilleuse Vie de Jeanne d’Arc (1929), for Marker first seeing this when he was seven years old “a face filling the screen was suddenly the most precious thing in the world,” or it be Falconetti or Louise Brooks or Kim Novak, as he puts it, “a film without a woman is still as incomprehensible . . . as an opera without music.” Hélène Chatelain’s, awakening in La Jetée is one of the most remarkable moments in all of cinema, a sequence of dissolves cause the still images to melt one into another until – an instant of motion – the fluttering of her eyelids, a twitch at the corners of her mouth, she looks directly into the camera and smiles. These six seconds are perhaps the most eloquent reflection on the nature of cinema that we have.

And the real heat in this countdown continues to fuel the cinematic radiator. At the end of this countdown in a bit over a week I will take stock in my own mind what the greatest essays in the entire exhautive 100 day have been and this supreme masterpiece of scholarship on LA JETEE will surely be in the running for poll position. Mind you it would be a diservice to express such sentiments publicly -after all we have had an amazing number of brilliant presentations and writing of the highest caliber, but Duane Porter has really raised the bar here. It is wholly fascinating, informative, in cinematic terms, experimental circles and of course in the political vein. Marker is an auspicious talent and writing about his life and his work is no easy assignment. Of course this is widely considered to be his masterpiece, and the voters of this countdown must be commended for placing it in such a well-deserved lofty position.

This piece is really definitive Duane. And those reference? Wow!! Take a bow!

This is, for me, maybe the single most educational essay on this list since, I admit, I knew nothing of the man who made the short film (which I’ve seen a couple or three times), nor much of the context. Oddly, while many of the list’s essays make me want to watch the movie at hand again, this essay makes me want to dive into everything else the man did. Fascinating person, great essay.

Awesome, brilliant review of one of the greatest science fiction works.

I have not ever seen or heard of this film until the essay about 12 Monkey’s and now the film has cross my path several times.

I have not read this whole review as of yet what I have read has offered great insight into a creative work of art well worth knowing about and investigating further…