by Joel

Let the Right One In (2008) is #95 in Best of the 21st Century?, a series in which I view, for the first time, some of the most critically acclaimed films of the previous decade. Along with this film, I will also be discussing the recent American remake, Let Me In (2010) and the book Låt den rätte komma in (2004) by John Ajvide Lindqvist, upon which both are based. There will be spoilers.

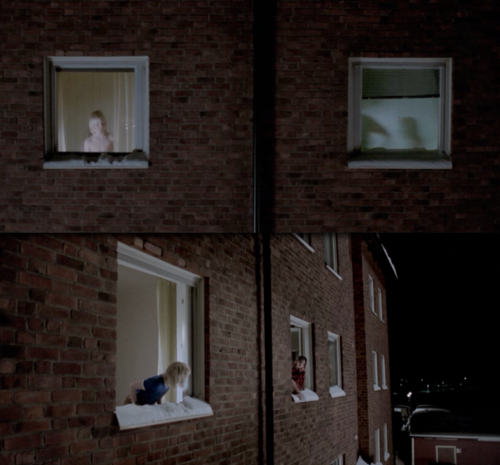

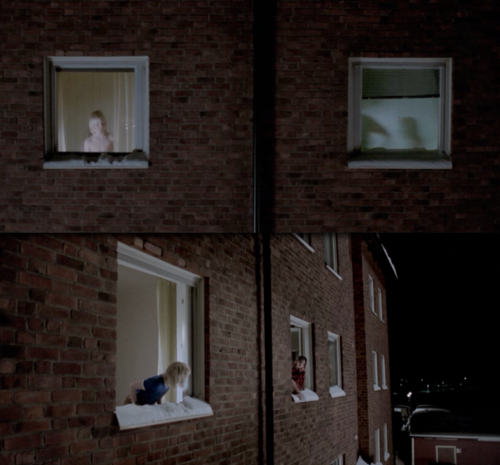

On a silent, snowy evening, a taxi pulls up to a deserted courtyard. The cold, lonely apartment blocks loom overhead, watching implacably, either unwilling to share their secrets, or without any secrets to share. But one frosted window at least has a human face in it – a little blonde boy, bare-chested, uneasily gripping a knife in one hand, the other pressed up against the glass, leaving a faint imprint, a marker to shout out impotently, “I was here!” Out of the taxi steps an older man and a young girl; though together, they still seem fundamentally alone – even that lonely boy upstairs has a warm, well-lit room behind him. On reaching their own room, the mysterious couple begin covering up their own frosted window with advertising placards, flashy but vapid come-ons ironically placed to block out the world. Down in the snow bank below, a haggard man pisses in the snow, glancing up at his peculiar neighbors and wondering, perhaps, who they think they are, closing themselves off like that. Don’t they know the world will already take care of that for them? Why seek isolation?

Because, as it turns out, there are some things worse than being alone. Such as joining together in brief, violent, frenetic couplings in which one person leeches the life out of another; or even worse, befriending and assisting this very leech, quenching your own isolation only at the expense of another’s life and happiness. These islands of humanity, floating in the impersonal sea of Blackeburg, both fear and desire human contact; they need it, but they know – or will discover – at what price this need can be fulfilled. Each of these individuals is as human as the next, but at least one is something else besides: a creature of the night, a blood-craving immortal, a murderous eunuch, a vampire. And this vampire, seemingly the most innocent of the four characters, that little girl who climbed out of the taxi, can only infiltrate your defenses if you let her enter your home – without permission, she will bleed from every orifice, so that even passivity breeds violence. Yet you must be careful before granting permission. It’s not enough to let just anyone in…

(more…)

Read Full Post »

Click on names for archives

Writers/Founders

Click on names for archives

Writers/Founders